The socioeconomic disadvantages for those struggling with sub-standard living and environmental conditions are prone to exhibit behavior that produces a substantial increase toward a diabetes diagnosis. The resources available to the communities and individuals that fall within these categories are not equal to those available to individuals that reside at other socioeconomic intervals. The burden experienced by these groups is also profound, thus increasing risk factors. An attention to wider prevention techniques may create an impact for those experiencing disadvantages in their access to care. Addressing the inequalities that exist for certain individuals and communities may affect the manner that we approach methods of diabetes prevention.

The authors say that "a more considerate and broad approach to diabetes prevention is needed," and that "...interventions should result from active collaborations with the communities in which they must be implemented." This can be difficult but still attempted, and as certain DPP efforts do reside at the local level where intervention is occurring, success can vary. How do existing DPP efforts differ from the approaches described by the authors, and what alternate collaborative approaches could be explored to help with intervention and implementation? Could digital health efforts also help in this situation?

Dear AMA community, I would like to begin by thanking you all for allowing me to join this important conversation and help guide the discussion. In dissecting the content of preventative medicine in the realm of socioeconomics, there are several patient pertinent factors that may be overlooked but are imperative to patient care. These elements include race, ethnicity, and culture which I would like to introduce to the panel.

Dr. Apovian and Dr. Beller alluded to a possible correlation between patient health and the patient’s race/ethnicity. In a report by Dr. Egede (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/...), he describes the 2002 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report which notes, “racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare exist and, because they are associated with worse outcomes in many cases, are unacceptable.”

In an effort to tackle this issue from the foundation: what may be the sources of disparity and how may these racial and ethnic disparities be addressed?

The disparities in the article include lower quality of care received, greater morbidity and mortality from various chronic diseases (worse outcomes), less use of preventive care services, differences in utilization of innovative medical technologies, and possible aspects of depression.

Possible causes for such disparity (though unproven empirically) include poverty and culturally-based patterns of human behavior related to such as language, customs, and thoughts (beliefs, values, attitudes).

Well, if poverty or culture are primary causes, then we should determine what it is about them that leads to poor engagement, activation and outcomes. Is it lack of access to high quality affordable care? Is it negative thoughts and emotions that result in maladaptive behaviors (e.g., avoidance or self-destructive tendencies)? Is it lack of affordable health food, safe housing, or poor health literacy, etc.?

I’d like to see research to identify common thoughts and emotions of people--in different SES, ethnic and racial cohorts--who avoid doctor visits or fail at self-maintenance. Are they afraid of something or feel hopelessly depressed for some reason? Is it distrusting of doctors? Is it a sense that there’s nothing to live for? Is it the idea that it is easier to avoid than to face life difficulties and self-responsibilities, instead of the idea that avoidance or inaction usually makes things more difficult in the long run? Is shame if not machismo? Is it rebellious anger because things are not the way one believes they should be? Once we begin to know these things, we can attempt to address them and help change beliefs and behaviors.

Problematic thoughts that lead to maladaptive behavior typically have qualities of catastrophizing, minimizing, wishful thinking, grandiosity, personalization, leaps in logic, and “all or nothing” mindsets.

If we develop a simple tool to gather these data in a research study, we could create protocols for dealing with them.

Dr. Beller, thank you so much for your response.

This is immensely multi-faceted and you noted many contributing aspects. I was specifically drawn to your mention of health literacy and I am curious as to how this can be applied to 1) prevention and 2) chronic care of patients.

Where can health literacy be improved, especially in handling diabetes?

Especially as a young professional entering this field and in working with patients with SES disadvantages, patients are seen clinically when their health significantly declines and may not follow up for subsequent checks. Is it possible to devise a means through which, in limited exposure to the patient, a thorough understanding of disease can be provided OR enough data can be collected to better study behaviors, trends, and gaps in care?

Thank you for bringing up this highly emotive and often politicised topic .. The role of demarcation and perceived social "value" in the world is often overlooked ,,as we are often our own worst enemies when it comes to bias and perception of value. ..Know thy self ... is often first step.

Good question, Sohayla. See this link health.gov/communication/liter...

Also, we envision a "curriculum network" that might be useful. It organizes instruction over time by serializing content in terms of prerequisites, i.e., what does someone need to know before s/he can understand the next unit of information.

I hear what you're saying, Marc! This very emotional topic gets involves ethics, cultural values, core beliefs systems, politics, and the positive vs. negative side of human nature. It stems from the very common irrational belief that (a) people's "inherent worth" can be somehow be objectively measured based on what they do, have, believe, and/or how they appear, and (b) that those judged more "worthy/worthwhile" somehow deserve a better life. The fact that this is so prevalent in our species is an key underlying reason we have such social discord in the world! I agree that if this daunting problem is ever to change, it has to start with self-awareness.

Following up on Clara's great question and my path-forward post, I believe the next question is: What can physicians (the AMA) and other clinicians do, if anything, to foster meaningful positive change? I contend that this requires thoughtful examination of daunting issues about the complexities of human nature, personal beliefs and values, and cultural and political influences, which are intermixed with genetic, biomedical, and even spiritual factors.

I can only speak from the point of view of obesity and prediabetes management where we see that there seem to be racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes for just about any treatment from diet exercise medication and bariatric surgery . Although my research team believes that these disparities relate to genetic differences, there is no proof that it isn't cultural or socioeconomic. There very likely could be influences from genetic plus cultural and socioeconomic issues. From this vantage point, we are not ready yet to fully outline an algorithm for care of differenct racial and ethnic groups because we are still exploring treatment outcomes. In the area of bariatric surgery we probably have the most data because it is much easier to collect than diet and exercise outcomes. African American groups do not do as well as Caucasian patients after bariatric surgery both in terms of weight loss as well as resolution of type 2 diabetes. The reasons for this disparity are still unknown. We cannot reliably inform health care which treatments should be offered to which patients and the risk benefit until these questions are answered.

I commend the work that Caroline and her team are doing help understand the underlying reasons for such disparity related to race/ethnicity.

This leads me to other questions: If their research discovers that there's a significant cultural and/or socioeconomic influence, what can be done about by the media and what can physicians and other clinicians can do to minimize the impact of those factors? What culturally- or socioeconomically-related differences are there in patients' thoughts (beliefs, attitudes) about bariatric surgery, diet, exercise, or whatever that might influence their decisions? How can a clinician discover such relevant patient thoughts and how can s/he help the patient to change them in a positive way?

Good morning everyone. Thank you for joining me in this discussion addressing socioeconomic disadvantages and behavioral interventions for diabetes prevention. I would like to kick off the discussion by asking everyone to initially address a challenge that they recognize in the approach to behavioral interventions for diabetes prevention in areas with socioeconomic disadvantages. How do these challenges influence the way individuals and communities view their stake in receiving care?

One obvious challenge is how to promote healthy eating and activity for a patient with socioeconomic disadvantages. Specifically, it's unlikely they would follow recommendations to buy healthy foods when unhealthy foods are advertised frequently, are typically less costly, are more readily available, and may taste better and be more filling (salt, sugar, fat). With exercise, they may have unsafe streets for walking, cannot afford exercise equipment, and, if a gym is available, membership may be too expensive. The problem may be compounded by local cultural influences in which obesity is accepted as normal, unhealthy diet is the norm, and a short lifespan is expected. In addition, there may a mindset of distrust, machismo, hopelessness, and a sense external control instead of self-efficacy. In other words, there may be negative economic, environmental, cultural, and psychological influences. These influences could result in negative beliefs about receiving care such as: “Why bother, I’m just going to be told do things I can’t afford;” “I don’t trust doctors…They really don’t care about me;” “A real man handles his own problems;” “They don’t appreciate the situation I’m in;” “It doesn’t matter what I do, things are out of my control;” “Who would want to live long with the life I have;” “Healthy foods don’t taste good/aren’t satisfying;” and so on. The challenge is to change these beliefs into ones the engage, e.g.: “I can trust what doctors tell me because they understand me and truly care about my wellbeing;” “There's nothing manly about dying of some illness because I didn’t take good care of myself…A real man accepts help when needed;” “I have the ability to do what’s necessary to be healthy…I’m in control of my own life;” “I want to live and enjoy life;” “There are healthy affordable meals I can prepare/buy that taste good and are satisfying;” “I can be more active without worry;” etc.

I’ve been thinking about a useful way to examine this very important issue, which is not only pertinent to diabetes prevention, but also to the prevention and treatment of just about any condition that requires patient self-management/engagement. It seems to me that a good way to begin is by answering two basic questions: What would be the current reality IDEALLY? How does the current reality DIFFER from the ideal and why? Once we answer these questions, we can discuss ways to transform current realities to be more reflective of the ideal.

How’s this for a start – Ideally, everyone should:

• Understand their health risks, problems, and suitable ways to deal them

• Have healthy eating patterns and healthy foods

• Exercise properly in a suitable place

• Access a PCP for physical exams, health risk assessments, advice, treatments, referrals

• Have a multidisciplinary care team (as needed) who follow a care plan that improves physical and psychological health through high-value methods

• Have beliefs, emotions and behaviors that result in wise health-related decisions and beneficial actions

• Monitor themselves

• Deal with distressing life problems rationally & effectively

• Live in a safe neighborhood with low crime, healthy environmental conditions, and stable housing

• Have competent, compassionate care givers (formal & informal)

• Have good social support from family, friends, community, etc.

Please share your thoughts on how things should be ideally and why they are not. We can examine what can be done to overcome the obstacles considering qualities of human nature and cultural values, as well as biomedical factors.

In addition to the list of ideal factors you mention, it would be ideal for health care providers to learn about the context in which patients are managing their care (i.e., food insecurity issues; food accessibility, etc.) and to incorporate this knowledge into care delivery. A more tailored approach to care, that takes into account the social/community barriers to self-management, would be ideal. Among the challenges to this scenario are: 1. How to efficiently deliver this information to providers who are often already swamped with information; 2. Current care guidelines do not provide guidance as to how to tailor interventions to patients based on social/community factors.

The list of ideals I presented is solely from the patient's point of view. Annemarie's inclusion of the clinician's perspective is terrific. If anyone can add to this, please do. I will compile a complete list with additional feedback.

This all points to the need for more interprofessional team-based care delivery models. Also, members of those teams will need to know how to leverage the insights generated by their own population health management solutions. Applying those data-driven solutions at a local level will impact change in subsets of populations.

How can this local model best be implemented?

The most prominent way I can think of is that the clinicians and healthcare providers are train members of the community in which they serve. They would be the prime members who can both provide care but also understand the population they are caring for. How can this best be fostered? Or, are there other ways to bridge the providers to the community?

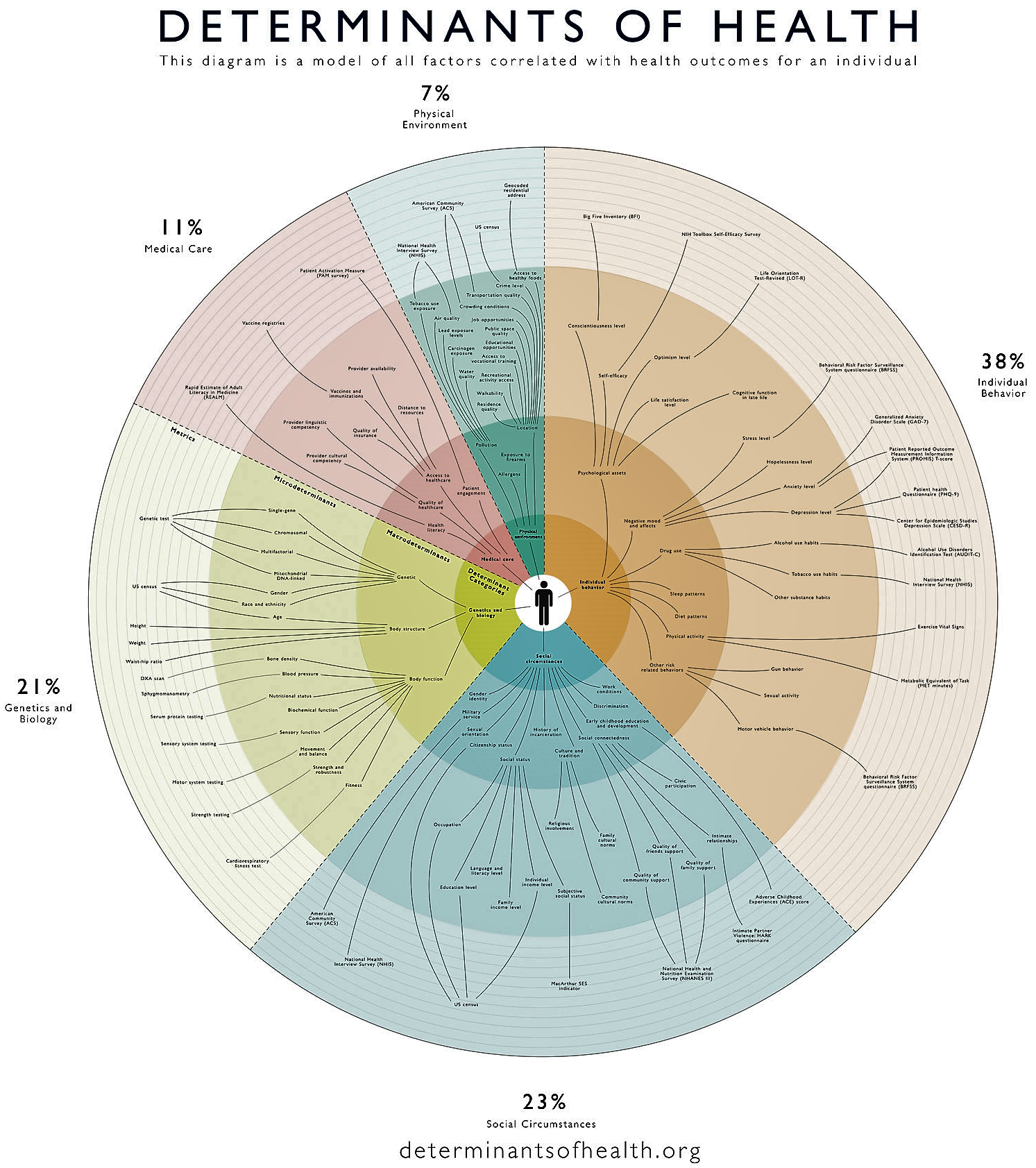

Sohayla’s and Joseph’s posts converge to create the idea that providers’ (clinicians’) understanding of the local population empower them to address social determinants of health (SDoH)-related issues, e.g., by enabling them to bridge their communities by sharing what they know. So, what types of knowledge would they share and how?

Well, if patient engagement and activation is a primary goal, providers could (a) share what they know about the ways people in their communities think and feel about the effects of SDoH influences and (b) apply this knowledge when making care decisions. Taking Annmarie’s comment into consideration, there needs an efficient, practical way to gain such knowledge and use it clinically.

Here’s an idea: What if providers asked each patient a few questions about how certain SDoH factors affects his/her emotions and health-related actions? Ideally, this would be a collaborative effort in which we define the questions and submit patients’ responses to a central repository for compilation, along with demographic metadata the would enable cohort analysis. I think this could become a useful research study and lead to guidance on how to tailor interventions to patients based on social/community factors. Just asking patients the questions, responding empathetically, and indicating recognition of the importance of SDoH on the patients’ lives could, in itself, help increase trust, engagement and activation.

Pending

The various community-based DPPs are all grounded in the original curriculum, but even the group nature of the program today is a variation from the original intervention - I think that has gone a long way to improve the reach of the program. Many have taken innovative approaches to reaching underrepresented populations. Some of the biggest success that I've seen come from the faith-based community. A great example is the Faith Community nursing program at Henry Ford; they've employed many innovative approaches to reach members of their community who may not otherwise touch the health system.