COVID-19 has introduced unique stressors to the health care community over the past year. The overall impact of COVID-19 on the health care workforce will likely have lasting effects in the years ahead. While the pandemic has opened up new avenues for innovation, it has also introduced great strain on many of our caregivers. Join us for a panel where we’ll discuss the evolving data on clinician burnout and well-being and provide insights into innovative strategies to combat clinician burnout for the long-term.

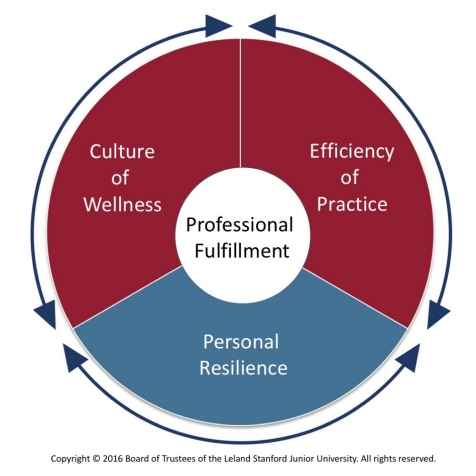

At the AMA, we position most of our burnout work using the Stanford Model of Professional Fulfillment but there are many frameworks that could be used to frame this issue and inform strategic planning and resourcing. Which frameworks are your favorite?

Good morning and welcome to our panel discussion! As we know the past year and a half has introduced many new stressors on the healthcare system and clinicians. As we move out of the pandemic, what do you foresee as stressors that will continue to contribute to clinician burnout that arose from the pandemic?

Thanks for kicking us off with this question, Laura, and really delighted to be part of the conversation. What's really interesting is that--based on some research that I've conducted--what we know is that frontline health care workers (HCWs) in NYC who were experiencing burnout in the year BEFORE the pandemic were those most likely to experience negative mental health outcomes like depression, generalized anxiety, and covid-related PTSD symptoms at the peak of the pandemic in April-May 2020. COVID has only magnified these issues, and rates of burnout at my institution continued to climb by the end of 2020- early 2021 as symptoms of psychopathology went down.... however, I do feel - through conversations like these and a ton that is in the literature right now, that there is more attention on this issue than ever before, and we cannot UNSEE this problem... I hope that we've initiated a formal era of prioritizing the health care worker as it is so clear how integral we are to this public health crisis.

What feels dangerous, and others might disagree with me, is the constant touting of HCWs as HEROES, a label that I think brings with it a great deal of cognitive dissonance when we simply don't feel heroic, especially back at the pandemic peak in 2020 when there was just so much death and helplessness that we all experienced. I think this messaging can actually fuel burnout, especially that "low sense of personal accomplishment" piece when this label just doesn't feel authentic....

How do others feel about the "health care heroes" narrative? I imagine to some it can be quite empowering... but for others, maybe we're missing the mark....

Thanks again Dr. Feingold for bringing up this important idea. I agree that it is a dangerous paradigm to call those who provide healthcare "hero's". As we know, hero's have super powers and can do anything. While those in medicine are people trying to help others in the best way they know. Just like people out in the community, our healthcare workers are parents, children, friends who have the same life stressors BUT also an added stress of daily exposure to the potential of a COVID infection and bringing it home to their loved ones.

Throughout the pandemic we have seen anxiety, depression, increased substance use, and even trauma. Many healthcare systems are concerned about staffing their hospitals as there are so many people that have left or retired early from healthcare. From what I have seen in the literature none of us should expect to see these psychological symptoms go away quickly. I have seen some articles that tell us that healthcare organizations will be dealing with the psychological fall out from COVID for years to come. This means healthcare organizations need to develop strategies that help to identify who's struggling, reduces stigma for care and improves accessibility so that it is easy for our providers to get the mental health services that they need.

Regardless of our roles in healthcare, we are all members of society. The pandemic highlighted a number of societal issues which will continue to affect healthcare for years to come. The list is long but includes social justice, diversity, equity, and inclusion, the role of misinformation, and lack of trust between various sectors of society. All of these will influence clinician well-being.

The “hero” label has turned to a negative and, as previously stated, is likely fueling burnout. As many of my colleagues have said, “Before, I was a “hero” working with limited supplies and support, and I did what I needed to make the best of a bad situation. Now, I am no longer a “hero” working with the limited support yet expected to do more with less because our institution(s) are still recovering from financial impact from the pandemic.” The work has not stopped, and the resources to perform at a high level are still limited. I hope our institutions recognize this and work at the ground level to support our clinicians with their input.

Let’s not forget that this fifth wave is rising, and a number of our colleagues are dealing directly with the pandemic and a rising number of COVID patients that they may not have had to deal with in the previous waves. Finally, a concern for our colleagues with young children is regarding the vaccine. Even if it prevents them from getting sick, they are worried that they may be asymptomatic and transmit it to their children too young to be vaccinated. The pandemic is not over, and the concerns for one’s family are still deep and getting less attention.

Many patients unfortunately delayed care for chronic medical conditions and preventative care throughout the pandemic. Several of my colleagues have shared how challenging it has been to manage medically complex patients (many via telemedicine) or in the inpatient setting while also managing the overwhelming influx of patients requiring care for covid during the various peaks of the pandemic. We've yet to see how delays in care related to the pandemic will impact long-term health outcomes and what stressors these will place on already stressed healthcare systems.

I am not sure whether this is exactly related to the pandemic or not, but healthcare seems to be facing the same staffing shortages that other industries are experiencing across the nation. The sudden rise in housing cost, an enormous influx of people into our state during the pandemic, and a shocking increase in cost of living is having a significant impact on our ability to gain and retain staff (nurses, techs, etc). Shortage of staff has been shown to directly impact the wellbeing of care teams, to a significant degree. As one of my goals is really to enhance efficiency of practice in my organization, I worry about lack of staffing. I think it will be a very big challenge to creatively improve efficiency with potentially fewer staff. I've heard this concern from other wellbeing leaders across the country as well. I'd be curious to hear from other panelists as to how they might be addressing this.

Dr. Wickersham, this is a really excellent point. I want to echo this in the context of mental health care, and the major gaps that existed for patients in receiving mental health services - even those already tapped into psychiatric services pre-pandemic. I have seen many patients in the inpatient psych setting who were admitted primarily due to psychiatric or substance-related decompensation in the context of pandemic-related stressors or an inability to seek / fear of seeking care.

One of the interesting issues we are learning again, as this is not new, is that it is very difficult to be a health care worker. And with the stress of Covid 19 and the huge demand, our personal health and wellness has been on hold, Many practitioners have not seen their own doctor for their own health issues and many practitioners have no one they identify as their family doctor. At our university, we started a program called Docs4Docs. Basically family doctors, even with completely full and closed practices agreed to take on a fellow doctor as a patient so that that persons health can be monitored properly. For it is a familiar saying that the shoemakers children have no shoes. Our ICU experts, our cardiologists, our respirologists etc all need to take care of themselves and have an objective, well trained family doctor to oversee basic screening and general health issues. We need our experts to be healthy as this pandemic continues to take its toll.

We also have some excellent websites, such as Resilience RX, part of The Rounds, where we can exchange important information, sharing best practices across the country encouraging social networks and social connectedness. For Covid is likely going to be with us for some time and we need to have the resources to cope with our own demands and intensity around work.

Is this something you openly talk about with your employees? If so, how do you frame this issue when discussing it? Is there a balance between your focus on the system-level drivers and individual resiliency?

Thanks for getting us started, Kyra! So, as most of us know - burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low sense of personal accomplishment and is a WORK-RELATED phenomenon rather than a mental disorder (and certainly not a personal failing).

While burnout is clearly driven by systemic factors within a work environment or institution, when not constructively mitigated, it can lead to poor outcomes for individuals such as depression, substance use disorders, loss of joy at work, desire to withdraw from the occupation, and even suicidality. In students and trainees (the population I’m a part of and work with most directly), it is also associated with a lack of professional behaviors (academic dishonesty, reduced likelihood to report medical errors).

I think a big problem in the PR of burnout is that it all too often is put on individuals as a personal problem, rather than a systems issue. The implication so often is, “this is YOUR problem” vs. "this is ALL OF OUR problem," and “this requires you to go get help, talk to someone, figure this out” vs. “we are going to hear you and support you in addressing some of the drivers of burnout and helping you cope optimally.” I think some of the most realistic and practical solutions are going to have to straddle this divide of “individual vs. systemic” interventions and really aim to address BOTH of these buckets- in other words, I think this is a false dichotomy....

One intervention we’ve rolled out at my institution is something called the PEERS program (Practice Enhancement, Engagement, Resilience, and Support). It’s a well-being program housed within the Office of Well-Being and Resilience, with a paid faculty advisor, that creates regular spaces within UME and GME with trained facilitators to process experiences, have a guided discussion, and learn an evidence-based positive psychology skill to cope with challenges. Topics include things like using strengths at work, practicing self-compassion, embracing gratitude, practicing well-boundaries empathy, etc. In the context of these sessions (about once monthly for residency programs) the facilitators often hear about systems-level issues that they can funnel to program directors or admin, while also creating a sense of community and teaching practical skills for learners to face future challenges.

Given the stat that approximately half of students, trainees, and practicing physicians experience at least one symptom of burnout, we absolutely need systemic solutions to get at the root causes while also equipping our health care workforce with the skills to adequately care for themselves, and each other, continually find meaning and joy in their work, and do so with the support of their institutions, teams, and larger cultures.

I couldn't agree with Dr. Feingold more. When we talk about burnout within our organization we need to focus on the systemic burnout drivers that promote distress and look to find strategies that help to target those pebbles and rocks. There are many broken processes that need to be updated. With so much focus on quality indicators of care, complicated billing procedures and increased technology, we can't just practice medicine the way we used to. It's also important for organizations to look at their policies and ask themselves whether those policies really align with a mission toward promoting provider well-being. If burnout is high within an organization, it's really important that the organization step back and ask, "what are we doing that is contributing to this distress?"

Certainly providers bring themselves into the health care arena but I would attest that people who go into medicine are some of the most resilient and gritty people I know. When organization strategies only focus on the individual it leads to more moral distress and can cause providers to feel angry.

With this in mind, it's important that organizations have a multi-prong approach to this body of work. One of the key strategies includes measuring the distress of your healthcare workers. In doing so, organizations demonstrate that they care enough to ask but also these results give organizations a foundation to build a strategy that is supported by the leadership of the organization. Another strategy we have adopted in our organization is using the framework of the IHI Joy in Work collaborative and having "What matters to you?" focus groups. These focus groups allow you to meet with frontline providers to learn about what matters to them in the work that they do, what gets in the way of the work that matters and finally to determine local and system interventions that need to be developed to address those pebbles and rocks that gets in the way of the work that matters.

Yes, Dr. Maclean! We need to say this loudly and clearly: HEALTH CARE WORKERS ARE SOME OF THE MOST INCREDIBLE, RESILIENT, AND MENTALLY STRONG PEOPLE ON THIS PLANET. Burnout is not due to a lack of resilience - it is due to a misalignment of values within our health care system that drives us to do work that is ostensibly far less meaningful and more burdensome than what we signed up for....

I couldn't agree more with all of your insightful comments! Organizations MUST strive to improve the systems we work in as the way to promote clinician well-being. Clinicians burnout because the systems they work in are broken. Similar to improving quality and patient safety, we cannot expect to move the needle on clinician well-being until we start addressing the systems issues driving the burnout.

The National Academy of Medicine formulates clinician burnout as an imbalance between job demands and job resources. As the attached figure shows, the external environment, the healthcare organization, and the frontline of health care delivery (clinicians and patients) determine clinician job demands and resources. They are filtered through an individual's characteristics which determines that individual's level of burnout and well-being. Therefore, both top down and bottom up approaches are relevant to addressing this problem.

Hey there, Neil! I really love that you shared this, and I love how this graphic depicts beautifully that all systemic factors filter through the lens of an individuals' unique experiences. What's more is that we must conceive of the absence of burnout and the presence of well-being as distinct concepts that may require different solutions. Addressing the drivers of burnout will not automatically result in the presence of well-being for clinicians; we would also benefit from tools, education/ knowledge, and TIME to explicitly pursue those things that makes each of us well (including factors within AND outside of work).

I like to refer to the IHI framework, the Quadruple Aim for healthcare, as a starting point for this conversation. Including the care teams' wellbeing in the framework for delivery of care inserts the importance of including care team wellbeing in decisions that are made at organizational levels. I think as wellbeing leaders, one of the most important things that we need to do is build relationships with the right people in our organization. Then, when we are discussing EHR and impact on teams; when we discuss workflows, when we discuss staffing impacts, when we discuss HR matters, etc., the wellbeing of the care teams is part of the language, part of the discussion. In my organization, I share my wellbeing leadership role with one other physician and we are on many different committees in our organization (including board committees and the Steering Committee for our EHR), and by participating, we are a constant voice for wellbeing in these spaces.

Thank you, Dr. Maclean. I really like the question you propose leaders ask themselves. "How are we contributing to this problem?" Also, love the idea of asking care team members, "what matters to you?" Engaging people in this way gets to those pebbles. As recently pointed out at a conference I attended, it is of great importance that when these questions are asked, that there is also followup. The leaders must come back and followup with people and let them know what is being done to address the pebble. And, if nothing can be done, why not. Thank you!

Pending

The National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience has several useful resources, including frameworks to ground wellness strategies. They complement the Stanford Model.

The Clinician Well-Being Knowledge Hub can be found here:

nam.edu/clinicianwellbeing/

A conceptual model which puts the patient at the center, surrounded by the clinician and the clinician-patient relationship is here:

nam.edu/clinicianwellbeing/wp-...

A conceptual model developed for the NAM's consensus study used a systems approach and included a feedback loop for continuous quality improvement to enable a learning health care system. The report can be accessed here:

nam.edu/systems-approaches-to-...

Report release slides including views of the conceptual model are here:

nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/201...

Connect

I really love the Stanford Model of Professional Fulfillment model. I think it is helpful and validating for learners to understand that their personal resilience is only a fraction of the equation. One of the favorite quotes I often hear doing this work is that “Culture eats strategy for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.”

I also find that in my work in teaching students, trainees, and physicians, one thing that people really want to unpack is, “What does physician well-being mean anyway?” We understand the ingredients of burnout relatively well (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low sense of personal accomplishment) - but what is well-being, really?

Herein lies the basis of the REVAMP framework, which stems from my years studying Positive Psychology, the science of well-being & human flourishing. REVAMP is an acronym & call-to-action for health care professionals to prioritize the ingredients of well-being in their personal and professional lives

R = Relationships (positive relationships with colleagues, patients, administrators, and close personal others outside of work)

E = Engagement (using our unique strengths in our work, finding flow in our daily routines, bringing an orientation of mindfulness to our work-life)

V = Vitality (possessing the energy to successfully engage in our work-life with vigor; e.g. adequate sleep, nutrition/diet, physical activity)

A = Accomplishment (embracing achievement as a non-zero sum game - How can we ALL win?; celebrating small wins and debriefing our successes)

M = Meaning (connecting with the larger purpose of our work, even when it feels monotonous; embracing the power and privilege of being so intimately involved in other’s lives)

P = Positive Emotions (noticing and savoring the positive affect that drives us and is central to our work; seeking gratitude in our day-to-day, deliberately cultivating positive emotions and embracing emotional contagion - making others’ days with our own positive affect.

Connect

As I've said before during other parts of this discussion, is clear to me that the absence of burnout is not the same thing as the presence of well-being. And the mental framework of enhancing well-being looks quite different than that of eliminating burnout.

I teach courses aimed at drilling home how we can use evidence-based practices to work toward each of these REVAMP elements in real-time, in our clinics, workplaces, and lives outside of medicine.

I'm curious: what do these REVAMP elements look like for you? Is there any particular element that stands out as being MOST CRITICAL for your own well-being? Which are the toughest to integrate?

**Also huge plug for Dr. Neil Busis' post and the National Academy of Medicine's Knowledge Hub!!

Pending

Stanford was at the forefront when they developed their 3 prong approach to wellness. They recognized that addressing burnout meant creating tactics that looked at leadership, policies and culture, the process of our work and finally tactics meant to enhance personal resilience. Even when this was developed, they recognized the larger onus of work is at the organizational level. Their model put physicians at the center. The organization I represent is very patient centric - our mantra's over time have included things like "each patient first", "just say yes" and "all for you". With that in mind, our approach put's patients at the center surrounded by physician vitality and then addressing the other areas similar to the Stanford model. It takes what Stanford has done and personalizes it to our core mission and purpose.

Pending

We use the Stanford Model of Professional Fulfillment in our wellbeing work in my organization. We find it to be an excellent framework not only for helping us with strategic planning and areas of focus, but also as a very useful tool for education. We have used this model to identify key areas where we need to do more work, and it has helped guide our overall plan. Recently, when presenting to our hospital board and executive team, it has been an excellent way to explain what it is that we really mean when we speak of care team, specifically physician wellbeing. As already pointed out by other panel members, this model also highlights that 2/3 of professional fulfillment are outside of one's own personal resilience. The largest area of work must come from the organization, creating a culture of wellness and enhancing efficiency of practice. Understanding this is key in moving real change. Resiliency is a smaller piece (1/3 of the pie), and we are, as pointed out already quite resilient as physicians.